In this lesson on Balagha, we are going to learn about the order of words in a sentence, especially a verbal sentence.

Table of Contents

Standard order

As you know from the grammar of verbal sentences in Arabic, the regular order of components in a verbal sentence is that the verb comes first, then the subject, then the objects, then the adverbs and then the prepositional phrases.

The subject comes near the beginning because it is the primary component of the sentence. The objects follow because they are an integral aspect of the verb, but not as important as the subject. The adverbs and prepositional phrases come at the end because they are non-integral details of the verb. Adverbs come before prepositional phrases because (as we discussed in the previous lesson on verbal details), they are special and more common types of verbal details.

Switching Words out of Grammatical Necessity

That’s the regular order and the reasons for it. But sometimes the subject, object and adverbs etc change positions and sometimes this is done out of necessity.

For example:

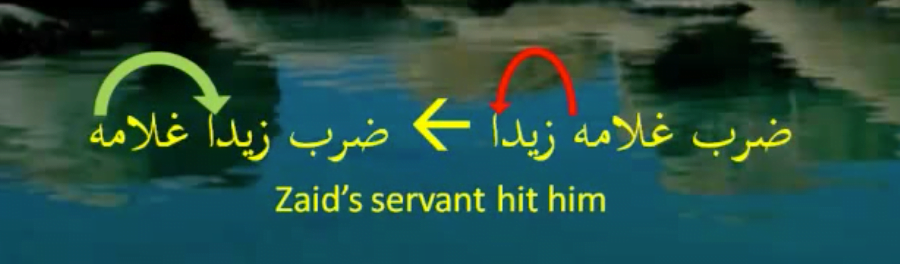

The subject has a pronoun that refers to the object, like ضرب غلامُه زيدًا (His servant hit Zaid). The “his” in this sentence refers to “Zaid”. As we learned from grammar, this type of sentence is illegal. In order to fix this, we can change the order and say: ضرب زيدًا غلامُهُ . In this new sentence the subject and the object have switched positions out of grammatical necessity.

Switching Words for Rhetorical Effect

In this lesson we want to learn why we switch positions even when it is not grammatically necessary.

Corrupted Meaning

The first reason is because although the regular order of words doesn’t cause a grammatical error, it does corrupt the intended meaning of the sentence.

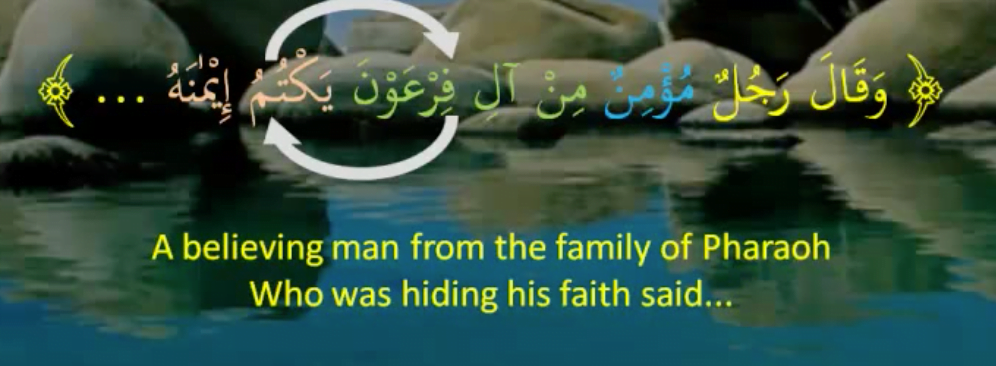

For example, Allah says:

Here we have the verb قَالَ, the subject رجلٌ, and the three adjectives/adjectival phrases for رجلٌ. They are: مؤمنٌ (he was a believer), مِن ال فرعونَ (he was from the family of Fir’own), يكتم إيمانَهُ (he was concealing his faith).

Let’s say you bring the phrase مِن ال فرعونَ at the end of the sentence. Now you have:

و قال رجلٌ مؤمنٌ يكتم إيمانَهُ مِن ال فرعونَ

Technically, this is grammatically correct and you are allowed to bring the sifah modifiers of a noun in any order. But now you have corrupted the meaning, because someone could get the impression that this is “a man” with two adjectives. The first is مؤمنٌ (he is a believer) and the second is يكتم إيمانَهُ مِن ال فرعونَ (he is hiding his iman from the family of Fir’own).

There are two problems. Now you think that:

- He is hiding his iman only from the family of Fir’own, and from no one else.

- And you don’t know that he is from the family of Fir’own. You have lost that fact.

Because of the corruption of meaning by changing the order of the words, we keep the order of words in the unexpected manner.

Integral Prepositions

Another situation where the order of words is changed is when a prepositional phrase is linked to a verb, and so you try to bring it as close to the verb as possible.

There are two types of prepositional phrases in terms of linking to a verb in a verbal sentence.

One is where the prepositional phrase introduces a detail that is non-integral to the verb.

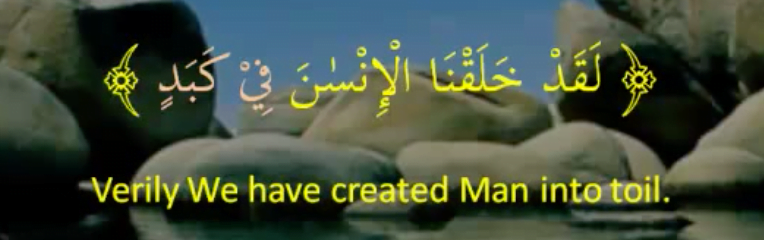

For example:

Notice that the verb خَلَقَ doesn’t require any detail introduced by في. في كبد is a non-integral detail of خلقنَا.

The other is where the prepositional phrases introduces an integral detail of the verb.

For example:

This is Yusuf (peace be upon him) talking.

Here the preposition has an impact on the verb’s meaning.

We say that عَنِّي is the صلة of تصرف. And when we give the meaning of صَرَفَ. We even say that صَرَفَ means this and صَرَفَ عَنْ means that. In fact, you will find صَرَفَ in the dictionary listed with all the prepositions that come after it, and slightly alter its meaning. Among them is عنْ. Such prepositions introduce details that are very much like objects. And for this reason, they deserve to be closer to the verb.

Focus

Another reason to switch the order of words in a sentence is to bring words you want to put focus on closer to the front of the sentence.

For example, we all know that Zaid usually hits Amr, but what if one day Zaid starts to hit Khalid for no apparent reason? In this case, we bring Khalid to the front of the sentence and we say:

The point of the sentence is Khalid. We know that Zaid exists, and we know that he hits somebody all the time, but we think it’s Amr. Because it is Khalid, it is Khalid that we want to put focus on, therefore we bring Khalid at the beginning. This is hard to translate into English. Often the best we can do is put stress on the word that has the focus. We say: Zaid hit Khalid!

It is interesting to compare the difference between bringing a verbal detail before the verb (from the previous lesson) and bringing it after the verb but before the other details. This is what we are learning in this lesson.

Remember we bring details before the verb to achieve restriction and to correct someone’s misconception. But we bring details after the verb, but still closer in order to achieve focus.

Let’s compare the translation in both cases. The regular version of our sentence is ضرب زيدٌ خالدًا (Zaid hit Khalid).

The in-front version is خالدًا ضرب زيدٌ (No, no. It was Khalid that Zaid hit).

The close-up version is ضرب خالدًا زيدٌ )Can you believe it, Zaid hit Khalid of all people!).

Rhythm and Rhyme

There are other reasons to change the order of the words in a sentence, like maintaining rhythm and rhyme.

For example, Allah says:

Part of the reason the subject موسى has been delayed, and other parts of the verbal sentence has been brought forward is so the sentence rhymes with the other verses in Surah Taha.

- Proceed to next lesson: Non-Informative Sentences: Wishes, Hopes & Desires

- Return to index page: Intro to Ilm Ul-Ma’ani

- Start free lessons: Sign Up for Free Mini-class