Welcome to our first lesson on ilm ul ma’aani (the main sub-science of ilm ul-Balagha).

In the first half of this lesson I would like give a brief overview of the Arabic language. How sentences work essentially, just so that we are on the same page. We are going to need some of this information in later lessons.

I am going to try to keep it so that even if you know zero Arabic, these lessons on ilm ul ma’aani will still be beneficial, inshaAllah.

In the second half we will actually do the introduction to ilm ul-ma’aani. That is, we’ll speak about what it is, how it fits in balagha and what we study in this science.

Table of Contents

Crash Course on Arabic Sentences

Brief Overview of how Arabic Sentences Work

If you take any sentence, it will have a primary verb. That primary verb will either be:

- The verb “to be” expressed as “is”, “is not”, “are”, “are not”, “am”, “am not”, “was” “was not”, “were”, “were not”, etc.

- Some other verb.

If the primary verb of your sentence is the verb “to be” then we are going to create a type of sentence in Arabic called a nominal sentence.

For those of you who know Arabic, this is called a جملة إسميّة.

If the primary verb is any other verb at all, we are going to create a type of sentence called a verbal sentence, or a جملة فعليّة.

Nominal Sentences

How do nominal sentences work?

Example: I am hungry.

In English, you have the subject. In this case it is just one word: I.

Then you have the verb “to be”. In this case it is: am.

Then you have the predicate. In this case it is: hungry.

The subject is what you are talking about, and the predicate is what you say about it.

In Arabic, it works very similarly. First you have the subject: I. In Arabic it is: أَنَا. You don’t have the verb “to be”, because Arabic doesn’t have that verb, so you skip it, and you go directly to the predicate. The word “hungry” in Arabic is: جوعان.

“I am hungry” is just أَنَا جوعان.

Issue in Nominal Sentences

It is pretty simple, but there is an issue here.

What if the sentence gets really long? Because in our previous example, the subject (what you are talking about), and the predicate (what you say about it), were both single words. But that is not always going to be the case. You get longer sentences because your subject and especially your predicate can be made up of nested phrases, and even nested sentences. There could be a high level of nesting especially in Arabic.

When you have a long subject and a long predicate, then how do you tell where the subject ends and where the predicate begins?

Because in Arabic there is no verb to tell you. Like in English you have: “The barking dog is in Zaid’s car”. How do you know what the subject is and what the predicate is?

It is easy! You just look for the primary verb; the verb “to be”. In this case it is expressed as the word “is”. Everything before “is” (the barking dog) will be the subject, and everything after “is” (in Zaid’s car) is the predicate.

Since Arabic does not have that verb, how do you tell?

This issue also exists in English to a certain extent. It comes up in the case of questions. If I were to turn “The barking dog is in Zaid’s car”, into a question, I would say: “Is the barking dog in Zaid’s car?” I pulled the “is” to the beginning of the sentence. Essentially, I no longer have the luxury of saying that everything before “is” is the subject and everything after it is the predicate. That is no longer the case. You see, this problem does exist in English. But it is just confined to the case of questions.

So, how do we figure it out in English? Nobody is confused when they hear this sentence. Everybody knows what it means, and what the subject and what the predicate is.

How? That is actually a difficult question.

If you think about it, you will realize that we know what the subject is and what the predicate is, given our experience with the different types of phrases in the English language. Because we know about all the possible phrases in English, based on our experience from childhood, we know that there is no other way to understand this sentence, other than making “the barking dog”, into one phrase, which eventually becomes the subject, and making “in Zaid’s car”, another phrase, which eventually becomes the predicate. The meaning is helping us out a little bit, but generally it is our understanding of English phrases that tells us. We don’t rely on where the “is” falls.

As for what we do in Arabic. One of the primary goals of Arabic grammar is to teach us the entire inventory of phrases in the Arabic language. There are about twelve of them. When we understand all of them and we have enough experience with all of them we will know that there is no other way to understand this sentence other than making:

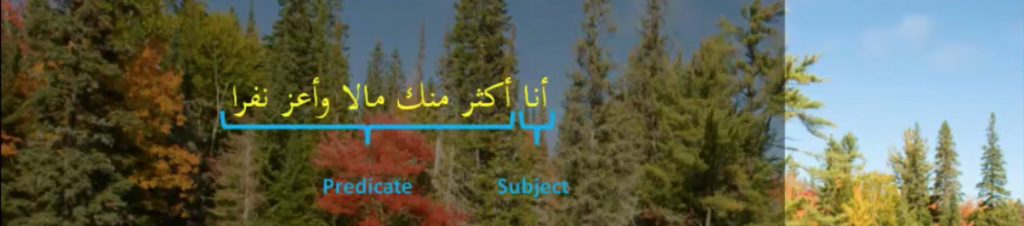

- أَنَا by itself, the subject of the sentence

- أَكْثَرُ مِنْكَ مَالًا وَ أَعَزُّ نَفَرًا turning that into a phrase and making that the predicate.

There is just no other way to combine these. You can’t say أَنَا أَكْثَرُ is a phrase and that becomes the subject. That’s not possible because there is no phrase like that. You can’t analyse a sentence like that.

Verbal Sentences

How do Verbal Sentences Work?

Now, verbal sentences are easy too. In English, we have “Zaid hit”. First we have the subject, then we have the verb.

The subject is who did it. And the verb is what did he, she or it do.

In Arabic the only difference is that the order is reversed. First you have the verb, then you have the subject.

“Hit” is ضَرَبَ so I’m going to write that first and Zaid is زَيْدٌ.

Zaid hit: ضَرَبَ زَيْدٌ.

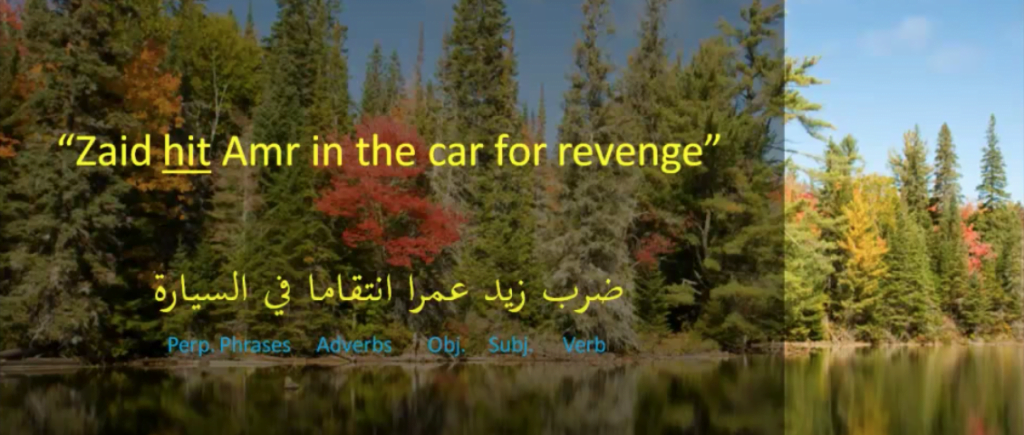

Apart from the subject and verb, a verbal sentence can have zero or more objects. E.g. Zaid hit Amr: ضَرَبَ زَيْدٌ عَمْرًا. In Arabic, just like in English, I am going to put the object عَمْرًا after both the verb and the subject.

We can also have adverbs. In English, I put the adverbs after the objects. In Arabic I do the same thing: ضَرَبَ زَيْدٌ عَمْرًا اِنْتَقَامًا (Zaid hit Amr out of revenge).

After the adverbs I can have prepositional phrases: ضَرَبَ زَيْدٌ عَمْرًا اِنْتَقَامًا فِي السَّيَّارَةِ (Zaid hit Amr out of revenge in the car).

I have to have a verb, I have to have a subject. I can have zero or more objects, adverbs or prepositional phrases. This is the general order in the Arabic language. First verb, then subject, then the objects, then the adverbs, then the prepositional phrases.

This is very similar to English; the only difference is that the subject and verbs swap places.

Issue in Verbal Sentences

But there is an issue here as well, just like with nominal sentences. The issue is that while in English I have to keep the order of the words, i.e. I have to say: “Zaid hit Amr”. I can’t just switch it around: “Amr hit Zaid”. Otherwise the meaning changes, but in Arabic I can. In fact, I can pretty much have any permutation of the words as long as I don’t mix up the order of words in a phrase, i.e. as long as I keep each phrase how it is. I can move words and phrases around and it really doesn’t affect the meaning in any major way. For example:

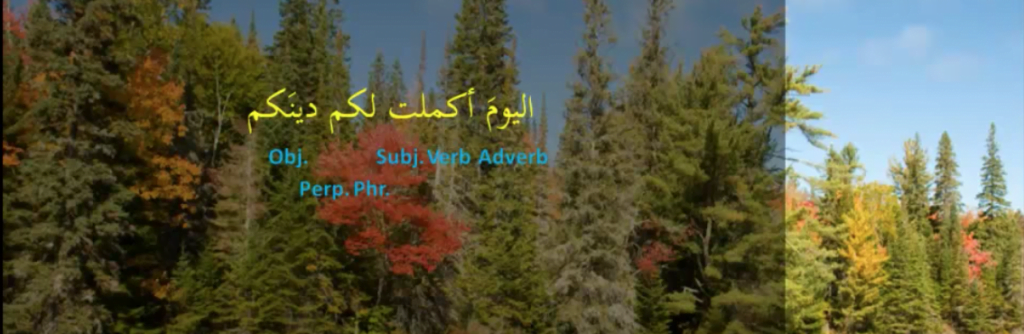

Here I have an adverb first, then the verb + subject, then a prepositional phrase, then an object.

Under normal circumstances you would expect to see: أًكْمَلْتُ دِينَكُمْ الْيَوْمَ لَكُمْ.

That would be the natural order. Here we see the order is mixed up and that is perfectly allowed.

The question then is: How do I know which of these words or phrases is the subject? Which of them is an object? Which of them is an adverb?

If the order won’t tell me necessarily, then how do I know if I can just switch around all the words. How do I know who’s doing the verb, who’s the one who the verb is being done to, and so on and so forth?

Notice, the meaning helps me. الْيَوْم can’t be the subject of the verb because it means “today”. Obviously, it is going to be an adverb. But that explanation only goes so far. In general, how do I know?

In English we have this issue to a limited extent also. What if I am writing poetry and I have the phrase “He she hates”. I can do that. It is legitimate to do that often. It happens all the time. You have the subject, then the object, then the verb. This is in order to keep the rhyme, rhythm and meter.

In this case how do I know who hates who? Did he hate her? Or did she hate him? How do we solve this in English?

We have different forms for the pronouns “he” and “she”. For “he” we have: he, him and his. For “she” we have: she and her. These different forms tell us what role the word is playing in the sentence.

We can say: “Him she hates”. i.e. she hates him. Or we can say: “He her hates”. i.e. He hates her. It might sound a bit awkward, but grammatically speaking, it is correct. We can say “Him she hates”. Now the meaning is determined, it is not confusing anymore.

In Arabic we have something similar, except it is not just restricted to pronouns. It is in almost every word. Every word has approximately three forms. E.g. if you take the word: الْيَوْم. You can say الْيَوْمُ, you can say الْيَوْمَ or you can say الْيَوْمِ. These forms tell you what role the word is playing in the sentence. The word is just الْيَوم. The vowel and the last letter tells you, whether it is the subject of a sentence, the object, the adverb, or whether it is part of a prepositional phrase etc.

Because the vowel on the last letter tells you, you can mix up the order and still understand what the sentence is saying. The second half of grammar (remember the first half is about phrases) is about this concept of the vowel on the last letter of a word. There is a lot to be discussed regarding that.

That was a crash course on Arabic sentences. There is really nothing to it. When you get advanced, there is a lot to talk about. Arabic grammar is pretty heavy, but at the basic level that is all there is to it. Just learn some vocabulary, and you can go ahead and make Arabic sentences.

Introduction to Ilm ul-ma’aani

Now that we have that under our belts, let’s do an introduction on ilm-il ma’aani.

Remember Arabic Rhetoric is divided into three sciences:

- Ilm ul-ma’aani

- Ilm ul-bayan

- Ilm ul-badee’

Ilm ul badee’ is just like the cherry on top. It is not really central balagha. The main concentration of balagha is ilm ul-ma’aani and ilm ul bayan.

What is ilm ul-ma’aani?

Ilm ul-ma’aani is the sub-science of Balagha (Arabic rhetoric) that discusses how to make sentences that are appropriate to ones current context, situation, circumstances and disposition of the audience one is speaking to.

Remember in grammar, grammar would take a verbal sentence and say you can mess around with the order of the words and the basic meaning is still the same. So, in a three word sentence there are six permutations that you could use.

Ilm ul-ma’aani comes along and says that of those six permutations, this is the one you should use. Based on your audience, what they are thinking, do they respect you, are they ignorant? What is your current situation, does your current situation call for brevity or does it call for going on giving a long speech, or does it call for being sort of sly, hidden? We leave it up to your audience to figure some stuff out. What does the current situation call for? What does the disposition of your audience call for?

Ilm ul-ma’aani tells you what to do with all those possibilities that grammar left you with. Grammar leaves it open. These are the six possibilities that are all valid. Ilm ul-ma’aani comes along and says ok grammar gave you these six possibilities, I am going to tell you which one is the best given your current situation.

Ilm ul-bayan will come along and say ok, well grammar left you with six possibilities, ilm ul ma’aani sort of chose one for you, but then if you have an idea that you want expressed there are still a million ways to express it. Especially in terms of clarity. Should you be literal or figurative? Should you just be straight up or do you use similes’ or metaphors or metonymies or synecdoche? Should you do any of that? That is what ilm ul-bayan will tell you. Of those vast ways and possibilities of expressing the thoughts in your mind, how should you express them.

It goes even a step further than ilm ul-ma’aani. in fact, often the relationship between ilm ul-ma’aani and ilm ul-bayan is compared to the relationship between the مفرد (single) and the مركّب (compound). Like words are single and sentences are compound (made up of words).

Ilm ul ma’aani is like the choice of various sentences and ilm ul bayan is like the choice of various ilm ul-ma’aani results.

Eloquence

In between Arabic grammar and Arabic rhetoric, there is a degree called eloquence. This is when one is able to avoid strange or ugly words, beautifully construct sentences, and avoid confusing the listener.

For a detailed handling of this, please access this tutorial which covers the topic of Arabic eloquence in its entirety.

The Eight Chapters of Ilm al-Ma’aani

It is divided into eight chapters. The earlier chapters are in consideration of the various parts of sentences.

Chapters 1-4 are all about sentences and what things can happen to the sentence and its components and which of those things you should do or not do. I.e. which of the six possibilities that grammar leaves you with, should you choose.

The remaining chapters 5-8 are about various other things:

Lesson Index

- In the first chapter we will study about creating sentences in general. Why would you create a sentence? i.e. why would you speak? What are the reasons in how you should do it.

- Lesson 2: Purpose of Sentences in Arabic

- Lesson 3: Emphasis in Arabic Sentences

- Lesson 4: Literal vs. Figurative in Arabic

- Tutorial: Summary of Predication

- Then we will talk about the subject, and all the things that can happen to it.

- Lesson 5: Mentioning and Omitting the Subject

- Lesson 6: Subject as a Personal Pronoun

- Lesson 7: Subject as a Proper Noun

- Lesson 8: Subject as a Relative Clause (موصول/ صلة)

- Lesson 9: Subject as a Demonstrative Phrase

- Lesson 11: Subject Made Definite by Al- (معرّف باللام)

- Lesson 12: Subject as a Possessive Phrase ( إضافة)

- Lesson 13: Subject as an Indefinite Noun (نكرة)

- Lesson 14: Extending the Subject Through Adjectives

- Lesson 15: Extension by Grammatical Emphasis

- Lesson 16: Extending the Subject by an AKA extension

- Lesson 17: Extension by Badal

- Lesson 18: Pronoun of Separation in Arabic

- Lesson 19: Hastening the Subject

- Lesson 20: Nouns in the Place of Pronouns and Vice Versa

- Lesson 21: Iltifat in the Quran (Switching Persons)

- Lesson 22: Intentional Misinterpretation (تلقي المخاطب بما لا يترقب)

- Lesson 23: Referring to Future Events Using Past Tense

- Lesson 24: Swapping Words (قلب)

- Then the predicate, and all the things that can happen to it. This is irrespective of whether it is a nominal or verbal sentence.

- Lesson 25: Omitting and Mentioning the Predicate

- Lesson 26: Types of Khabar in Arabic

- Lesson 27: Conditionals 1 – إن for Certainty instead of Doubt

- Lesson 28: Conditionals 2 – إِنْ and إِذَا Followed by a Past Tense Verb

- Lesson 29: Conditionals 3 – لَوْ Followed by a Future Tense Verb

- Lesson 30: Predicate: Indefinite, Definite, and Specific

- Lesson 31: Hastening the Predicate and Delaying the Subject

- In the fourth chapter we will talk about what can happen to the objects, the prepositions, the prepositional phrases and the adverbs in a verbal sentence. We will talk about what can happen to those and what you should do in certain various circumstance.

- Lesson 32: Introduction to Verbs and Verbal Details

- Lesson 33: Omitting the Direct Object

- Lesson 34: Verbal Details: Advancing a Detail

- Lesson 35: Order of Words in Verbal Sentences

- Restriction – Using the word “only”, should you say: “I only have one” or should you say: “I don’t have anything but one”? What are the various forms of restriction and how should you employ them?

- Non informative sentence – Like questions etc.

- Conjunction – Should you join two sentences with a conjunction or should you put a period and start with a capital letter again?

- Lesson 10: Fasl and Wasl in Arabic Rhetoric

- Brevity – Should you be brief and concise or should you go on and on, or should you keep your speech at a normal length? There are certain situations that call for various lengths of how long should you go, i.e. there are various cases that call for brevity and there are various cases that call for going on and on.

Addendum to Lesson 1

In the final section of this lesson on ilm ul-ma’aani we are going to give a slightly different introduction to ilm ul-ma’aani. You can think of it like an addendum to lesson 1. It is a continuation of lesson 1. I just want to introduce ilm ul-ma’aani in slightly different words so you get a slightly different perspective. We might get a deeper understanding of what the science is.

You have come to this section of the website to learn ilm ul-ma’aani and what I’m assuming that you have graduated from Arabic grammar and Arabic verb conjugation, etc, and you know how to speak valid Arabic.

Now what we want is to put you in front of an audience and ask you to deliver your message to them. Whether it is your best friend of whether it is a group of people you have never met before, it doesn’t really matter. The point is we are now getting you to deliver your message to an audience.

How do you do that?

You could just use the Arabic that you have just graduated from. Since you’ve graduated from it, you are going to speak valid Arabic, but it is also going to be very basic Arabic. You can imagine someone who has learned English for the first time and if you put them into a debate scenario and you ask them to debate with a group of people, they are going to speak valid English, but they are not going to have much emotion or they are not going to be able to articulate themselves in ways that you and I would be able to articulate ourselves. Their debate is not going to be as effective.

Similarly, when we ask you to stand in front of an audience and deliver your message to them, if you have just graduated from Arabic, you will be able to do it, but it won’t be as effective.

Ilm ul-ma’aani wants to teach you how to be effective and speak appropriately.

In order to do that, first you have to size up your audience. You have to ask yourself some questions. What is their level of intelligence? What is their level of receptiveness to you? There are a lot of questions you can ask. You really size up your audience. Who are they? Then what ilm ul-ma’aani is going to do is say that ok you have learnt all that about them. Now based on that here is what you should do. It is going to teach you how to speak effectively to your audience. How to speak with emotion. How to articulate yourself appropriately, which is appropriate to your current situation.

How does ilm ul-ma’aani do that?

Ilm ul-ma’aani says that you have a sentence that you want to deliver to your audience. We don’t want to change the meaning of that sentence. We don’t want to change the purpose of that sentence. Your message is going to stay the same. But still, there are a lot of things that can happen to your Arabic sentence. They won’t change the meaning, but there are things that can happen, e.g. emphasis. You can emphasize your sentence. Or the ordering of words. You can mix up the order of words. Remember we said that it doesn’t change the basic meaning of the sentence. You can rearrange the words. You can omit certain words and leave it up to the audience to figure out what is hidden. That might not make sense in English, but that happens in Arabic, etc.

There are a whole slew of things that can happen to your sentences in any language that don’t change the message.

What ilm ul ma’aani wants to do is go through all the things that can happen to your sentence and it wants to tell you under what circumstances to use that thing and under what circumstances to not use it.

Here is how it goes about doing that. It does that in 8 chapters. Chapters 5-8 are just 4 of those things that can happen to your speech:

Number 5 for example is restriction. E.g. I only have one sister, so I can say it like that: “I only have one sister”, or I can say: “I don’t have any sisters except the one”. There are a lot of ways you can deliver that one message. Under certain circumstances the first sentence is more appropriate. Under other circumstances the second sentence is more appropriate. You are building ways to articulate yourself. That is restriction.

Similarly, there is another thing that can happen to your sentence, which results in your sentence becoming non-informative, for example asking a question.

Then there is conjunction. When should you separate two sentences with a period, or connect them using a conjunction. E.g. “I have one sister. I have one brother”. Or should you say: “I have one sister and I have one brother”?

And finally, brevity. When should you be brief? And when should you expand upon what you are saying and deliver more details. These are all things that can happen to your speech that don’t change the message but there are things that can happen, so ilm ul-ma’aani wants to teach you when to use which, and when not to.

The remaining ones are combined in 4 chapters. These are the first 4 chapters in ilm ul-ma’aani:

- Predication

- Subject

- Predicate

- Objects, Adverbs, Prepositional Phrases, etc

The first chapter predication talks about all the things that you should consider, all the things that can happen even before you speak your sentence. When you are making the intention when you are making your sentence. When you are coming up with it.

Then the subject, all the things that can happen in the subject of your sentence. And all the things that can happen in the predicate. Remember in verbal sentences the predicate is made up of the verb and additionally or optionally objects, adverbs and prepositional phrases etc. There is a chapter about those adverbs and prepositional phrases and objects.

We will begin with the first chapter in the immediately following lesson. It is called predication, and this is where you are just intending to create a sentence to deliver your message. We want to talk about all those things that you should take into consideration having sized up your audience. Now that you know what your audience is like, what are the things you need to consider when creating your sentence.

- Proceed to the next lesson: Purpose of Sentences in Arabic and Tanzeel

- Start free lessons: Sign Up for Free Mini-class