In this lesson on Balagha, we are going to learn about conditional statements (شرطيات).

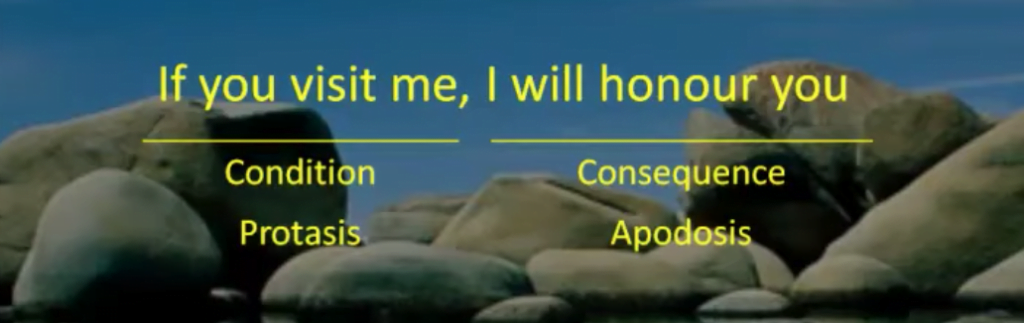

A conditional statement, as you know is one in which you have a condition and a consequence.

For example:

“If you visit me” is the condition, and “I will honour you” is the consequence.

In more formal terminology you can call the condition the protasis, and you can call the consequence the apodosis.

In Arabic, the condition is called the شرط and the consequence is called the جزاء.

You may be wondering why we are discussing conditionals in the chapter on predicates. Conditionals are primarily associated to predicates. You can see this by rearranging our example into a more fundamental form.

For example: I will honour you if you visit me.

“I” is the subject of our sentence, and “will honour you if you visit me” is the predicate. Notice that the conditional is simply a qualifier that we have added to the predicate.

We have already learned a lot about conditionals from Arabic grammar.

The words that indicate on condition and reward in Arabic are called adawaat ash-shart (أدوات الشرط). Some are particles and some are isms.

idh and idha are clearly isms, but for the purpose of these lessons we’ll just use the phrase “particles of condition” in a loose sense. Keep that in mind.

Now, in balagha we are going to look at it from a different point of view.

Table of Contents

Particles of Condition in Arabic

First of all, remember that in Arabic, there are four main particles (or agents) of condition (أدوات الشرط). Which one we use in a sentence, depends on the situation.

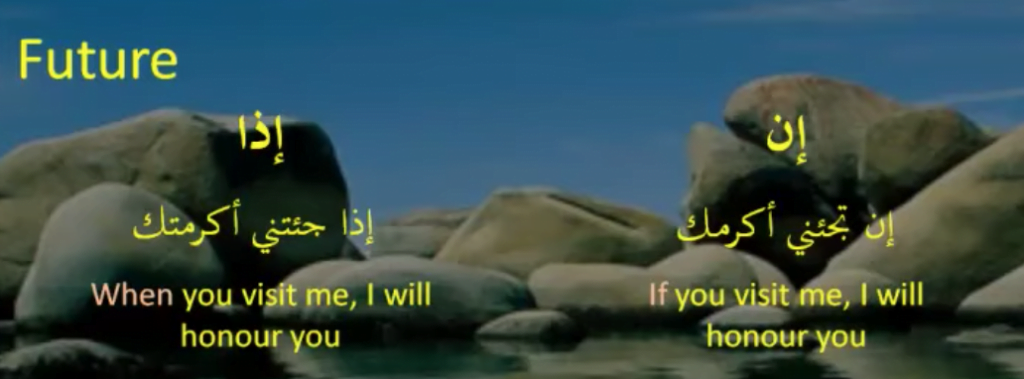

If we are talking about an event in the future we will use either إن or إذا.

If we don’t know if the action is going to happen or not, i.e. we have some doubt, we use إن. For example: إنْ تجئني أكرمك (If you visit me, I will honour you).

If we do know whether the event is going to happen or not, i.e. there is certainty, we use إذا. For example: إذا جئتني أكرمتك (When you visit me, I will honour you).

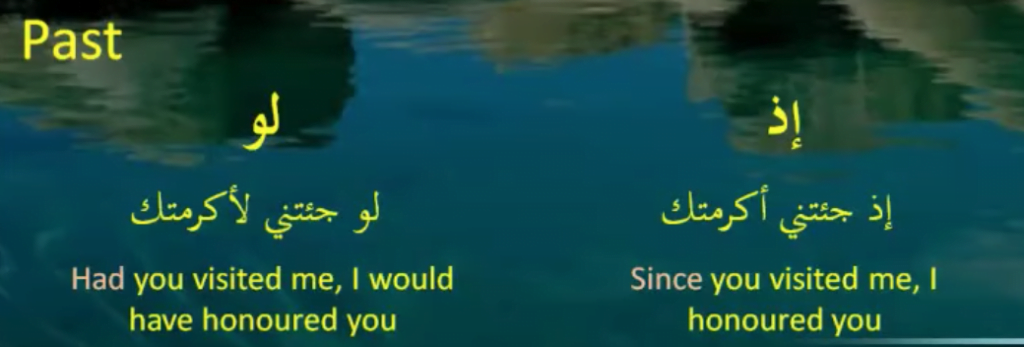

If we are talking about an event in the past, we will use either إذ or لو.

Here we don’t consider the level of doubt, because there is no doubt. The thing already happened. What we look at is if it actually came to pass or not.

So if it happened, we use the word إذ.

For example: إذ جئتني أكرمتك (Since you visited me, I honoured you).

If it did not happen, we use لو.

For example: لو جئتني أكرمتك (Had you visited me, I would have honoured you).

In conclusion إن and إذا are used for future, so the verb that follows them should be a مضارع. We also learned that إذ and لو are for past, so the verb that follows them should be a ماضي.

Furthermore we learned that إن is for doubt and إذا is for certainty, and we learned that إذ is for affirmative and لو is for negative.

Anomalies within the Adawaat ash-Shart

What often happens is that we will run into anomalies, where these rules are “broken”.

- At times إن will be used for certainty instead of doubt.

- إن and إذا will be followed by past tense verbs.

- إذ and لو will be followed by future tense verbs.

So here we have just mentioned 3 popular anomalies. Let’s look at each one in turn and examine why this anomaly happens. And what rhetorical benefits it yields. The rest of this lesson will focus on the first anomaly only.

إن for Certainty

The first anomaly we are going to look at is إن being used for certainty.

Remember إن means “if”, and you use it when you are not sure whether something is going to happen or not.

Like “If I get too much work tomorrow”. Obviously, that is something you cannot be 100% sure about.

But sometimes what happens is that you are absolutely certain that something is going to happen, yet you still use إن.

For example: “If the earth is still spinning tomorrow”.

Clearly chances are that the earth is still going to be spinning tomorrow. You can say there is pretty much 100% chance, but you are still using “if” even though it is a matter of certainty.

Pretend to Not Know

Now the first reason to do this is to pretend you don’t know something.

For example: if your wife gets a call from someone she really doesn’t want to talk to, you say: “Hang on, I’ll give her the phone if she is available”.

You know she is available but you pretend there is doubt, for whatever motive.

Speak According to the Listener’s Belief

Another reason to use إن for certainty is if the thing is certain, but not according to your listener.

For example: if you are introducing someone to Islam, you might say “If what I am saying is true”. Of course what you are saying is true, but your listener doesn’t know that. So according to their understanding, you use إن because for them this is an occasion of doubt.

Reduce Listener from Knowledge to Ignorance

Another reason to use إن for certainty is to reduce someone who knows, to the level of someone who doesn’t know.

For example, let’s say you are talking to a father and son. You tell the son: “If this is your father then you shouldn’t talk back to him”. You are admonishing the son. The son knows that this is his father, but he doesn’t act according to this knowledge. As a result you can reduce him from the level of knowledge to the level of ignorance, and speak to him as if he didn’t know the fact in the first place. So instead of saying “Since he’s your dad”, you say “If he’s your dad”.

From the Realm of the Possible

Another example of using إن for certainty:

Imagine two employees are talking and one of them says: “I will try to help you tomorrow, if the earth is still spinning by then”.

He is implying that the work is so impossibly strenuous, that it makes outrageous things, like the earth stopping from spinning, seem completely possible.

What he can also be implying is that the work is so hard that it can make impossible things happen. Like destroy the world for example.

All of this is designed to exaggerate the level of work, by associating it with another impossible phenomenon.

Rebuke Listener by Implying his Actions are from the Realm of Impossibility

Another reason to use إن for certainty is to rebuke your listener by implying that his actions are from the realm of impossibility. Now this is interesting, and it is hard to understand without an example.

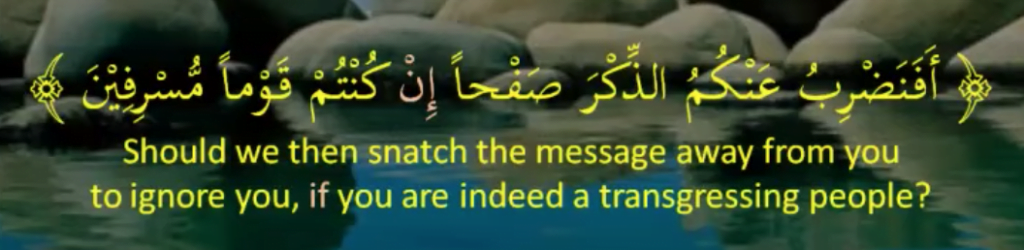

To see an example of this, we turn to Surah Zukhruf under a different qira’at, where Allah says:

Notice that the qira’at of Hafs is actually أَن, but this different qira’at is إِنْ كُنْتُم.

So the Quraysh were people who transgressed, therefore this is an occasion of certainty, not doubt. There is no doubt that the Quraysh transgressed, yet Allah still says: “If you are a people who have transgressed”.

The idea here is to show that given all the signs Allah has shown them, it is pretty impossible to remain transgressing. So the fact that they do transgress, although true, is being brought to the level of impossibility. Thus, ridiculing them for doing it.

Informally you can say it like this: “Look at all the signs I have given you through the Qur’an. So at this point it is pretty impossible for you to remain transgressors. If per chance you are still ignorant enough to transgress, then should I take away the very Qur’an that would help you come to the right path?”

Render the Listener Speechless

Another related reason for using إن for certainty is in order to overpower your listener in an argument, and render him speechless.

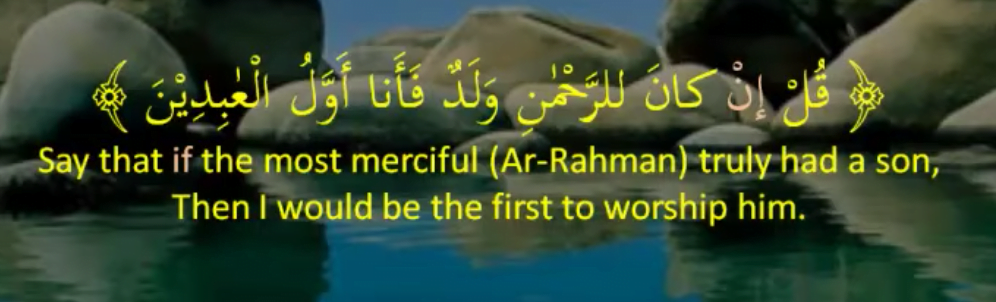

For example: Allah says:

So Allah having a son is an impossibility, let alone a doubtful matter. Yet here the word إن is being used. The idea is that it is so impossible that if it is to be mentioned at all, it can only be mentioned hypothetically. Not only that but furthermore, you don’t even have to keep arguing that Allah has a son, because if He did, I would be the first to worship that son. So not only has Allah having a son been restricted to the realm of the hypothetical, but the listener has been rendered completely speechless because we have covered all scenarios, possible and impossible. There is nothing more for him to say.

In the next lesson we will look at the second anomaly.

- Proceed to next lesson: Conditionals in Arabic (Part 2)

- Return to index page: Intro to Ilm Ul-Ma’ani

- Start free lessons: Sign Up for Free Mini-class