In this lesson on balagha we are going to do a quick overview and then turn our attention to the chapter on conjunction and disjunction.

Table of Contents

Brief Overview on Ilm ul-ma’aani

Balagha, translated as Arabic rhetoric is the science of the Arabic language that teaches us how to articulate our thoughts in an appropriate and convincing way, given our circumstances and given who we are talking to.

The reason we study it is to appreciate the beauty of the Qur’an. It is a pretty advanced science studied after Arabic grammar and Arabic morphology, and I would say it is four or five times larger than grammar. Some of the major imams of this science include, Allamah Sakkaki and Shaykh Abdul Qahir Jurjani, among others.

Balagha is made up of three sub-sciences:

- علم المعاني Ilm ul-ma’aani – helps us choose the best structures to convey our thoughts

- علم البيان Ilm ul-bayaan – helps us choose the best figures of speech

- علم البديع Ilm ul-badee’ – is the cherry on top that teaches us some literary devices

Ilm ul-ma’aani is divided into eight chapters and we have got to half way of chapter 2, talking about the subject of a sentence. What I would like to do in this lesson is skip to chapter 7 and do that first.

Introduction on Conjunction and Disjunction

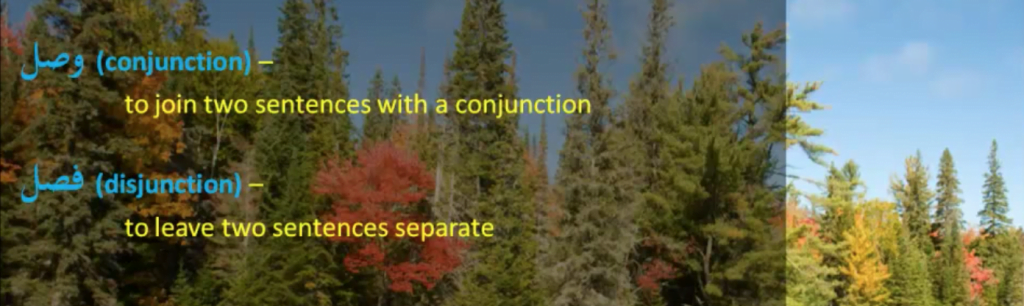

Chapter 7 in the books of balagha is called الفصل و الوصل. It talks about whether to join sentences with the conjunction. This is called وصل. Or to leave them as separate sentences. This is called فصل.

Actually, it is much more than that, because Arabic does not have any punctuation or formatting as you might be aware. You don’t have periods or commas or semi-colons or even paragraphing. It is all inferred from the conjunction or disjunction of sentences.

When we study this chapter, we are actually studying the entire concept of punctuation, paragraphing and organizing our discourse. Even in English, that is the essence of rhetoric.

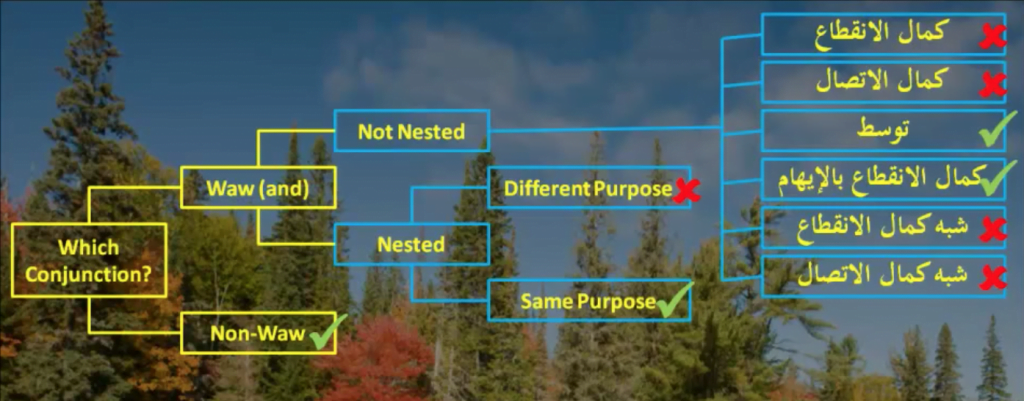

The name of the game is to determine whether to join two sentences with the conjunction or to leave them as separate sentences.

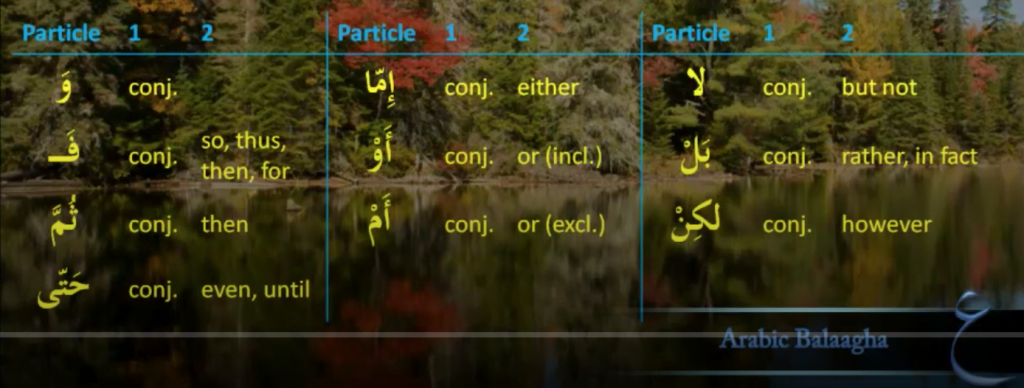

The first thing to consider is which conjunction you want to use. If you want to use anything other than و (waw) you are free to do so. That is because the Arabic language has about ten conjunctions.

Most of them have two functions:

- To join two sentences, i.e. to be a conjunction

- To give some additional benefit

For example: the word ثُمَّ means “then”.

“I got to work, then I opened my briefcase”.

“Then” is:

- A conjunction

- Gives the benefit that the first sentence happened before the second sentence

This isn’t true for waw which means “and”. Waw tells you that the two sentences are joined together, but it doesn’t give you any benefit beyond that. It is kind of like a comma in English.

Therefore, if you want to join two sentences with anything other than waw, it is okay, because like we said the additional benefit you get from the conjunction is a good enough reason to use it.

But if you want to use waw, the next thing to consider is if the two sentences are nested within a greater sentence or not. If the sentences are nested, you can only join them if they both have the same purpose and function within the greater sentence.

Let’s take an example: “How can you still be mad when I have proven my innocence and I said I was sorry?”.

Here we have two nested sentences.

- The first sentences is: I have proven my innocence

- The second sentence is: I said I was sorry

The first sentence is giving the reason why you shouldn’t be mad at me: because I am innocent.

The second sentence is also giving a reason why you shouldn’t be mad at me: because I am sorry.

Because they both have the same function in the greater sentence, and the same purpose, we can join them with waw. In fact, we should join them with waw. But if the two sentences don’t have the same function, it is important to keep them separate. In English it is like putting a period, or otherwise keeping the sentences separate.

If the sentences are not nested, instead they are independent clauses, then the next thing to consider is how much the two sentences have in common, in order to determine whether you are going to join them or not. This is where the bulk of the discussion lies.

There are six categories here.

Generally, the idea before we get into the six categories is that if the two sentences have so much in common that they are pretty much saying the same thing, then you don’t connect them with waw, because they are too similar. I.e. they are already too interconnected. If the sentences are too different then there is no reason they should be connected, so you don’t connect them with waw here either.

كمال الإنقطاع (Complete Disharmony)

Let’s start with the first category. This is where two sentences are completely dissimilar. The rule is that you don’t join them with waw. Again, because you can only join things that have something in common to begin with. Let’s look at two ways a pair of sentences would be so dissimilar.

1. Informative or Non-informative Value

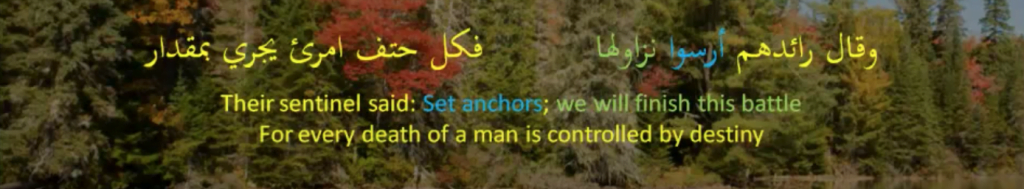

The first way is that one of the sentences is informative, while the other is non-informative. For example, the poet says:

- أرسوا is a command, so it is a non-informative sentence

- نزاول is an informative sentence

Therefore, it is not appropriate to join the sentence with waw. But be careful because sometimes the sentence can look informative, but it is actually non-informative. And sometimes vice versa also. Like رحمه الله (May Allah have mercy on him). It looks informative but it is a du’a and therefore it is non-informative.

2. Nothing in Common

The second way a pair of sentences are too dissimilar is if they are both informative, or both non-informative but they have nothing in common.

For example: Zaid sat and Amr called his father.

You see how awkward it is to join these sentences, considering there is nothing in common between them. It is really weird and of course this will be based on context and based on your judgement.

In English, when we are talking about two sentences and whether to join them or not. If the second sentence is a completely separate thought related to the first only by association, we tend to use parentheses. If the second is like a side note that adds detail to the first sentence, we tend to use hyphens. If the second is a completely separate idea, but carrying on the same line of thought we put a period. If it is starting a completely different thought, we start a new paragraph.

In Arabic, we signify all of these cases by simply omitting the waw.

كمال الإتصال (Complete Harmony)

This is the opposite of the previous category. This is where the two sentences are too similar. The second sentence is emphasising the first or elaborating on the first, or giving the reason for the first. In these cases, the rule is that you do not join the sentences with waw, because you can only join things that need joining. These sentences are too similar to begin with.

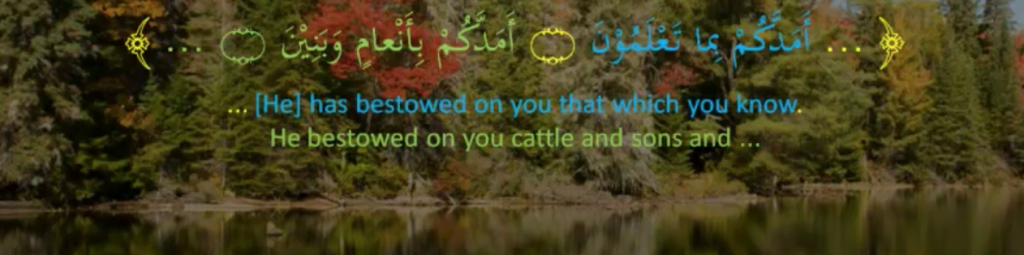

Let’s take a look at an example. Allah says:

- The first sentence is: أَمَدَّكُمْ بِمَا تَعْلمونَ (He helped you with what you know)

- The second sentence is : أَمَدَّكُمْ بِأَنْعَامٍ وَبَنِيْنَ (He helped you with cattle and sons and …)

The second sentence is merely elaborating on the first sentence. It is not conveying a brand-new idea. So joining the two with waw is not appropriate, because of how similar they are.

In English, sometimes we would use semi-colons, sometimes we would use colons, depending on the situation.

توسط

This is where the two sentences are different enough that they need to be joined. We say they have some تغاير. And they are similar enough that joining is actually appropriate. We say they have تناسب. In this case we join the sentences with waw.

For example, Allah says:

- The first sentence is: يُخَادِعُونَ اللهَ (They tried to deceive Allah)

- The second sentence is: هُوَ خَادِعُهُمْ (Allah answers their deception)

Notice that both sentences speak about deception, so they are similar. Yet one speaks of a group trying to deceive Allah, while the other speaks about Allah answering their deception. So, they are different, therefore they can be joined with waw.

What makes two sentences similar enough that you can join them? And what does it mean for two sentences to be similar?

Obviously, there are two things you are talking about, the two subjects, and they must have some common factor. And, the two things you say about them, i.e. the two predicates, must also have a common factor.

Like in the example, Allah says: يُخَادِعُونَ اللهَ وَ هُوَ خَادِعُهُمْ. The two subjects are similar, because in the first sentence, what is the subject, in the second sentence it is the object. And what is the object in the first sentence is the subject in the second sentence.

The predicates have something in common too. One is deception, and the other is answering the deception. The two are related.

This common factor is called a جامع. The books of balagha go into extreme depth talking about the جامع. The discussion is very detailed, and frankly it’s not for the faint of heart. In fact, it is the understanding of this جامع that really defines a rhetorician. My humble opinion, at the end of the day, is that it is all based on your common sense. Every situation is different. So, we are going to leave this detailed discussion.

كمال الإنقطاع بالإيهام (Complete Disharmony with Misunderstanding)

This is where the two sentences are completely unrelated. You wouldn’t expect to put a waw (based on what we have just learnt). But the thing is that if you don’t put a waw it will result in a corrupted meaning.

For example, let’s say I ask you: “Do you think I am going to fail the test?” You respond by saying:

[incorrect]: لا أَيَّدَكَ اللهُ [correct]: لا وَ أَيَّدَكَ اللهُ- Your first sentence (لا) was an informative sentence. You are saying: No, you won’t fail.

- Whereas the second sentence (أَيَّدَكَ اللهُ) although it looks informative, it is actually non-informative, because you are giving me a du’a : May Allah help you.

We just learned from كمال الإنقطاع that we shouldn’t put a waw between these sentences. But if you don’t put a waw the two sentences will read: لا أَيَّدَكَ اللهُ, which actually means “May Allah not help you”. See how the meaning is corrupted. So, we are supposed to leave the sentences separate, but doing so results in a corrupted meaning, thus we join them and we say: لا وَ أَيَّدَكَ اللهُ

شبه كمال الإنقطاع (Pseudo Complete Disharmony)

This is kind of along the same lines as the previous category.

This is where the two sentences are neither too similar, nor too dissimilar. Like in توسط, it seems like you can go ahead and put a waw. I.e. you can join them. But the thing is that if you put a waw, it will result in a corrupted meaning.

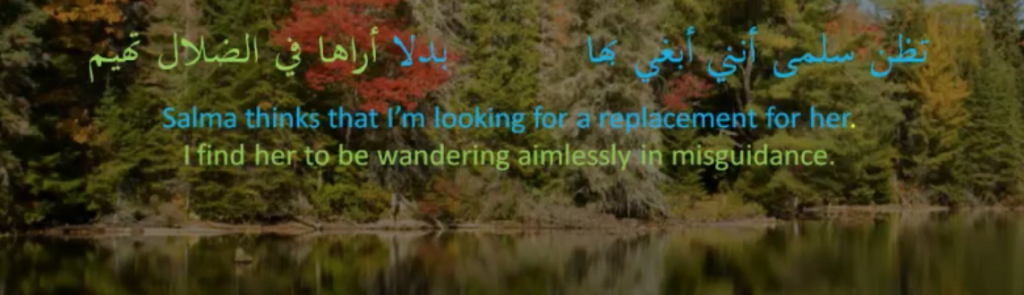

For example, the poet says:

- The first sentence is: تظنّ سلمى أنني أبغي بها بدلا (Salma thinks that I’m looking for a replacement for her)

- The second sentence is: أراها في الضلال تهيم (I find her wandering aimlessly in misguidance)

Notice it is perfectly appropriate to join these two sentences with waw, based on the rules we just learned about توسط.

But the thing is that if you put a waw, you might end up with the following meaning: “Salma thinks I am looking for a replacement for her, and she thinks that I find her to be in misguidance”. One might get the impression that the sentences are nested like that. Whereas, of course they are not. So, we have to keep them separate, and not put a waw.

شبه كمال الإتصال (Pseudo Complete Harmony)

The final category is a special one. This is where you have two sentences. The first is a statement that warrants a question, and the second is an answer to that question.

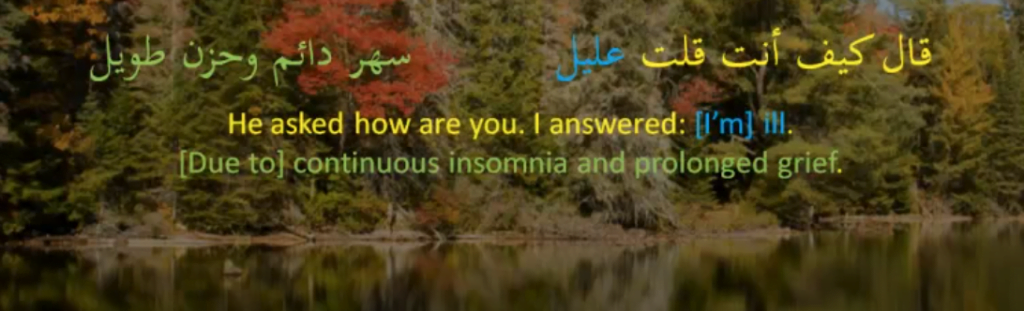

For example, the poet says:

- The first sentence is: عليل ([I’m] ill). Then someone might ask, “Why? What is wrong?”

- The second sentence is an answer to that: سهر دائم و حزن طويل ([Due to] continuous insomnia and prolonged grief).

Pre-empting a question like this and answering it, in balagha is called إستيناف.

There are also reasons why you would want to pre-empt a question and not to wait for the audience to ask it. I.e. by just going ahead and answering it yourself. But the point is that the sentence that warrants a question, and the sentence that answers it, will not be connected with waw, because they are already so interconnected, given this relationship.

That was a pretty advanced chapter in balagha. I have tried to simplify it as much as possible.

One last point is about the conjunction waw. In this entire lesson we have been assuming that the waw means “and”, but in the Arabic language waw actually has approximately twenty functions. These are listed in Ibn Hisham’s book مغني اللبيب عن كتب الأعاريب, which by the way every student of advanced grammar should have.

Sometimes you might find a waw between two sentences, where you wouldn’t expect to see it. It is probably because it is serving one of these other functions. It is not the “and” that you expect. For example, one of the functions of waw is to act as a period and start a new sentence. That is something to keep in mind.

The books of balagha end the chapter on فصل and وصل with حال (the circumstantial adverb). Here is an extraordinarily detailed discussion on حال

- Proceed to next lesson: Subject Made Definite by Al- (معرّف باللام)

- Return to index page: Intro to Ilm Ul-Ma’ani

- Start free lessons: Sign Up for Free Mini-class