In this lesson on Balagha, we are going to talk about the types of predicate in Arabic, or the various forms the predicate (musnad) can take. Such as being a noun, verb, phrase or sentence.

Table of Contents

How Many Types of Predicate are there in Arabic

The predicate of an Arabic sentence can come in all possible forms. It can either be a sentence (جملة) or it can be a non-sentence (مفرد).

If it is a sentence it can either be:

- a nominal sentence (جملة إسميّة)

Example: زيد أبوه قائم

Notice that أبوه قائم is a nominal sentence.

- a verbal sentence (جملة فعليّة)

Example: زيد قام

Notice that قام [along with its internal pronoun] is a verbal sentence that goes on to become the khabar for Zaid at the front.

If the predicate is a non-sentence it can be:

- a noun (اسم /ism/)

Example: زيد قائم

Notice that قائم is an ism.

- a verb (فعل)

Example: زيد قام or just قام

Notice that قام [in consideration of its internal pronoun] in both examples is a verb.

- a phrase

Example: زيد قائم أبوه

Notice that قائم أبوه is a phrase.

These are the various forms a predicate of a sentence can take.

In balagha we want to know, what is the purpose of each of these. And why would we use one over the other?

Just as a side note before we continue. You may be wondering about the difference between the predicate being a sentence (a verbal sentence in particular), and the predicate being a verb. After all, every verb constitutes a verbal sentence. Like in زيد قام, the predicate is a verb, but it is also a verbal sentence.

First of all, when we say the predicate can be a verb, we are contrasting that to the predicate being a noun. And when we say the predicate can be a sentence, we are contrasting that to the predicate being a non-sentence. So, it is a different perspective. (More on this in a minute under the heading “force”).

Second of all, if you take something like دخل زيد في الدّار.

The subject here is زيد, and the predicate is دخل في الدّار.

Now دخل في الدّار is a verbal sentence, just not a nested verbal sentence. So here the predicate is a verb, but it is not a nested verbal sentence.

Sentence vs. Non-Sentence

Predicate as a Sentence

The first question is: why would the predicate be a sentence vs. a non-sentence?

After all, in a sentence the subject is what you are talking about, and the predicate is what you say about it. What you say about something need hardly be a sentence in and of itself.

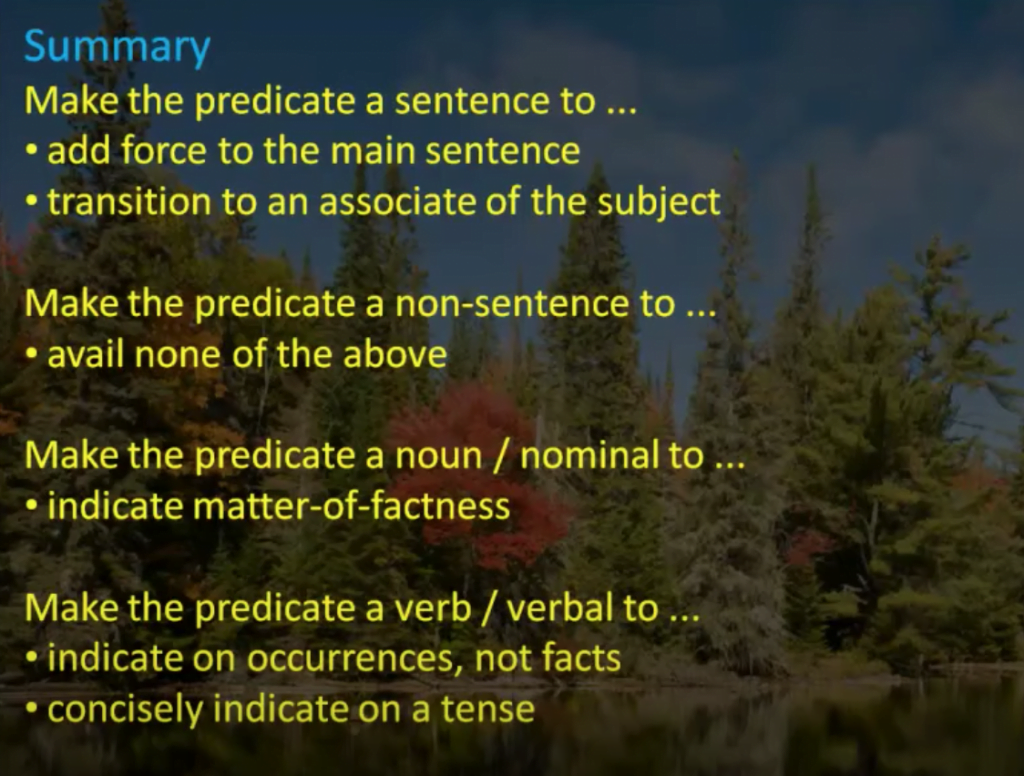

There are two major reasons for bringing the predicate as a sentence as opposed to a non-sentence.

Force

The first is to stress and strengthen the main sentence.

For example: if we say دخل زيد في الدّار(Zaid entered the house).

The predicate is not a nested sentence.

But if we say زيدٌ دخل في الدار, now the predicate is a nested sentence.

The second sentence carries more force.

There is a disagreement among the imams of balaga as to why a nested sentence gives more force.

Some of the scholars say that when you say زيدٌ دخل في الدار.

First you have a subject-predicate relationship between the subject زيد, and the predicate دخل في الدّار.

But then you have another subject-predicate relationship within the predicate. That is between the pronoun of دخل which again refers to زيد, and the rest of that sentence.

You have two instances of entering the house being attributed to زيد. This double predication results in force.

But other scholars says no, what if you have a sentence like زيد ضربته (Zaid, I hit him).

Here the nested sentence does not contain predication towards زيد. There is no double predication. Not for زيد anyway. Yes, there is still force. So you can say as an answer to that, that there might not be double predication for زيد, but there is still double predication on the whole. However, that is a bit of a weak answer.

What these scholars say is that when you start off your sentence by saying زيد, you have just put the listener in anticipation of something being said about زيد. And then you bring a nested sentence in which you provide the bulk of your statement about زيد. So preparing the listener to expect something about زيد is what adds force to the sentence.

In either case, remember that the force is on the predication, and the sentence as whole. Not on the subject, nor on the predicate. So, translation of زيدٌ دخل في الدار would be something like “Zaid did enter the house”. Notice the emphasis on “did”.

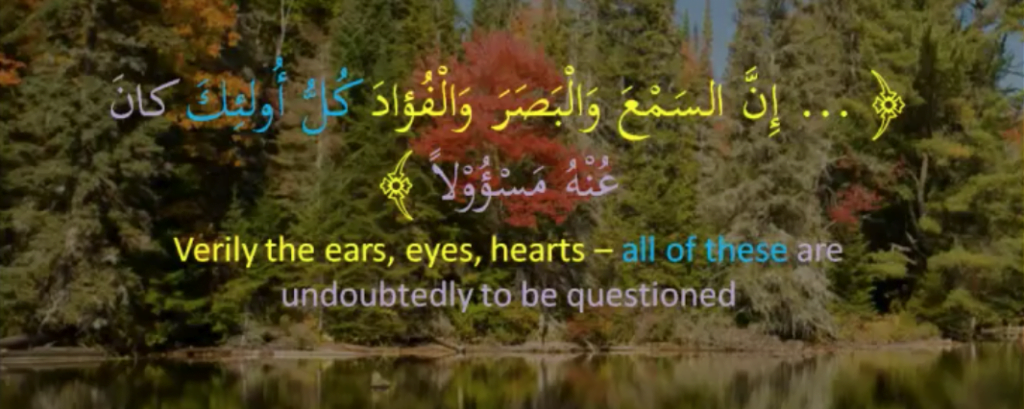

Take an example from surah Israa’, Allah says:

Notice in this sentence that the subject is as السمع و البصر و الفؤاد, and the predicate of this subject is a nested sentence.

The subject of this nested sentence is كلّ أولئك, which refers to السمع و البصر و الفؤاد.

We have double predication.

But yet, further, the predicate of this nested sentence is yet another sentence. The subject of this nested sentence is هو, which refers to the كلّ أولئك, which in turn refers to السمع و البصر و الفؤاد.

We have a triple predication for our ears, eyes and hearts being questioned. This adds tremendous force to this statement. Force that wouldn’t be achieved through a non-sentence predicate.

Transition

The second reason to bring the predicate as a sentence as opposed to a non-sentence is to facilitate the transition of the predicate from being about the subject to something being associated to the subject.

For example: زيد أبوه قائم (Zaid his father is standing).

Here we began the sentence by talking about زيد, yet once the predicate came, we realized that زيد was merely a stepping stone, and the sentence is really about “his father”.

This is different from a non-sentence version, such as زيد قائم أبوه.

The sentence version is translated as “Zaid, his father is standing”.

And a non-sentence version is translated as “Zaid is such that his father is standing”.

What we learn from this is that using a sentence for our predicate is for one of the two mentioned purposes. And using a non-sentence is to avoid either of the two purposes.

Actually, using a non-sentence for your predicate is the default. The only reason you would opt to use a sentence is to achieve one of these two benefits. There are other benefits as well.

Nominal vs. Verbal

Assuming that our predicate is a sentence, what is the difference between using a nominal sentence and using a verbal sentence?

The thing about verbs is that they are linked to a tense (past, present, future). Verbs inherently indicate on something happening, i.e. an occurrence. Whereas nouns don’t indicate on something happening, they indicate on something simply being the case.

For example: if we say زيد ينتقم. (Zaid takes revenge/ is taking revenge/ will take revenge/ takes revenge with some frequency). The point is that his revenge is an event, or a series of events.

But if we say زيد هو منتقم, using a nominal sentence, then this means that “Zaid is one to take revenge”. Meaning, he is vengeful in essence. It is not an occurrence. It is a fact.

Noun vs. Verb

Given that our predicate is a non-sentence now, we are switching gears here. What is the difference between nouns and using verbs?

As we discussed comparing nominal sentences to verbal sentences just now. Verbs indicate on occurrences, whereas nouns indicate on facts.

If we want to show that something happened, or is happening or will happen or that it happens with some frequency, we will use the verb. But if we want to show that something doesn’t merely happen, rather it is simply the reality and the fact of the matter then we would use a noun.

The same principle we learned regarding nominal sentences vs. verbal sentences applies to nouns vs. verbs.

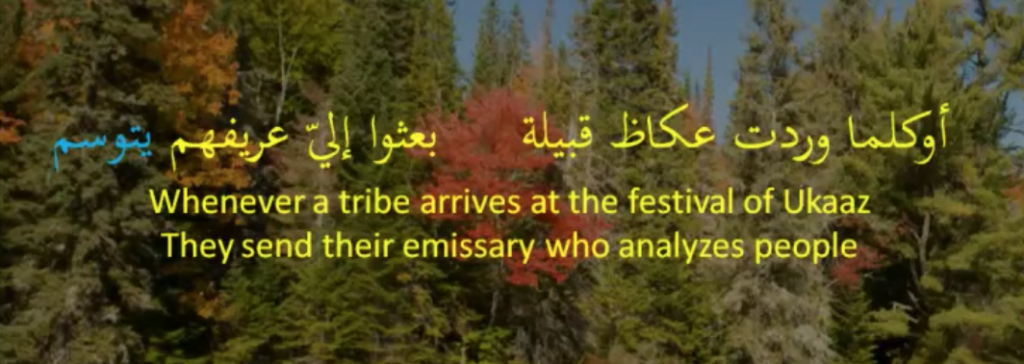

The example of this, we refer to the poet who says:

Ukaaz used to be an annual festival for the various tribes of Arabia. Among other things they would recite poems and vie against each other in that regard. Many tribes had an emissary who would manage their foreign affairs, whom they sent out to analyze people of other tribes. Such an emissary is known as the عريف of a tribe.

The poet is boasting about how brave he is, and how many people he has killed by saying that the عريف of all these tribes would look him up and down, over and over again, because he is like Arabia’s most wanted or something.

The point of the couplet is the last word يتوسّم. This is a sentence, whose subject is the implicit هو, and whose predicate is the word يتوسّم.

The poet is saying that every time a tribe comes to the festival of Ukaaz, their emissary looks me up and down all the time. The point being that these people keep looking at me every so often. Over and over again. It is not a fact of life that they are looking at me. It is a recurrence that keeps happening over and over again.

Summary

- Proceed to next lesson: Conditionals (Part 1)

- Return to index page: Intro to Ilm Ul-Ma’ani

- Start free lessons: Sign Up for Free Mini-class